October 27, 2014

The Bureaucratic Failure Mode Pattern

When we try to take purposeful action within an organization (or even in our lives more generally), we often find ourselves blocked or slowed by various bits of seemingly unrelated process that must first be satisfied before we are allowed to move forward. Some of these were put in place very deliberately, while others just grew more or less organically, but what they often have in common, aside from increasing the friction of activity, is that they seem disconnected from our ultimate purpose. If I want to drive my car to work, having to register my car with the DMV seems like a mechanically unnecessary step (regardless of what the real underlying reason for it may be).

Note that I’m not talking about the intrinsic difficulty or inconvenience of the process itself (car registration might entail waiting around for several hours in the DMV office or it might be 30 seconds online with a web page, for example), but the cost imposed by the mere existence of the need to report information or get permission or put things in some particular way just so or align or coordinate with some other thing (and the concomitant need to know that you are supposed to do whatever it is, and the need to know or find out how). Each of these is a friction factor; the competence or user-friendliness of whatever necessary procedure is involved may influence the magnitude of the inconvenience, but not the fact of it. (Other recursive friction factors embedded in the organizations or processes behind these things may well figure into why many of them are in fact incompetently executed or needlessly complex or time consuming, but that is a separate matter.)

Over time, organizations tend to acquire these bits of process, the way ships accumulate barnacles, with the accompanying increase in drag that makes forward progress increasingly difficult and expensive. However, barnacles are purely parasitic. They attach themselves to the hull for their own benefit, while the ship gains nothing of value in return. But even though organizational cynics enjoy characterizing these bits of process as also being purely parasitic, each of those bits of operational friction was usually put there for some purpose, presumably a purpose of some value. It may be that the cost-benefit analysis involved was flawed, but the intent was generally positive. (I’m ignoring here for a moment those things that were put in place for malicious reasons or to deliberately impede one person’s actions for the benefit of someone else. These kinds of counter-productive interventions do happen from time to time, and while they tend to loom large in people’s institutional mythologies, I believe such evil behavior is actually comparatively rare – perhaps not that uncommon in absolute terms, but still dwarfed by the truly vast number of ordinary, well-intentioned process elements that slow us down every day.)

Because I’m analyzing this from a premise of benign intent, I’m going to avoid characterizing these things with a loaded word like “barnacles”, even though they often have a similar effect. Instead, let’s refer to them as “checkpoints” – gates or control points or tests that you have to pass in order to move forward. They are annoying and progress-impeding but not necessarily valueless.

We are forced to pass through checkpoints all the time – having to swipe your badge past a reader to get into the office (or having to unlock the door to your own home, for that matter), entering a user name and password dozens of times per day to access various network services, getting approval from your boss to take a vacation day, having to fill out an expense report form (with receipts!) to get reimbursed for expenses you have incurred, all of the various layers of review and approval to push a software change into production, having to get approval from someone in the legal department before you can adopt a new piece of open source software; the list is potentially endless.

Note that while these vary wildly in terms of how much drag they introduce, for many of them the actual amount is very little, and this is a key point. The vast majority of these were motivated by some real world problem that called for some tiny addition to the process flow to prevent (or at least inhibit) whatever the problem was from happening again. No doubt some were the result of bad dealing or of an underemployed lawyer or administrator trying to preempt something purely hypothetical, but I think these latter kinds of checkpoint are the exception, and we weaken our campaign to reduce friction by paying too much attention to them – that is, by focusing too much on the unjustified bureaucracy, we distract attention from the far larger (and therefore far more problematic) volume of justified bureaucracy.

Let’s just presume, for the purpose of argument, that each of the checkpoints that we encounter is actually well motivated: that it exists for a reason, that the reason can be clearly articulated, that the reason is real, that it is more or less objective, that people, when presented with the argument for the checkpoint, will find it basically convincing. Let’s further presume that the friction imposed by the checkpoint is relatively modest – that the friction that results is not because the checkpoint is badly implemented but simply because it is there. And yes, I am trying, for purposes of argument, to cast things in a light that is as favorable to the checkpoints as possible. The reason I’m being so kind hearted towards them is because I think that, even given the most generous concessions to process, we still have a problem: the “death of a thousand cuts” phenomenon.

Checkpoints tend to accumulate over time. Organizations usually start out simple and only introduce new checkpoints as problems are encountered – most checkpoints are the product of actual experience. Checkpoints tend to accumulate with scale. As an organization grows, it finds itself doing each particular operation it does more often, which means that the frequency of actually encountering any particular low probability problem goes up. As an organization grows, it finds itself doing a greater variety of things, and this variety in turn implies greater variety of opportunities to encounter whole new species of problems. Both of these kinds of scale-driven problem sources motivate the introduction of additional checkpoints. What’s more, the greater variety of activities also means a greater number of permutations and combinations of activities that can be problematic when they interact with each other.

Checkpoints, once in place, tend to be sticky – they tend not to go away. Partly this is because if the checkpoint is successful at addressing its motivating problem, it’s hard to tell if the problem later ceases to exist – either way you don’t see it. In general, it is much easier for organizations to start doing things than it is for them to stop doing things.

The problem with checkpoints is their cumulative cost. In part, this is because the small cost of each makes them seductive. If the cost of checkpoint A is close to zero, it is not too painful, and there is little motivation or, really, little actual reason to do anything about it. Unfortunately, this same logic applies to checkpoint B, and to checkpoint C, and indeed to all of them. But the sum of a large number of values near zero is not necessarily itself a value near zero. It can, instead, be very large indeed. However, as we stipulated in our premises above, each one of them is individually justified and defensible. It is merely their aggregate that is indefensible – there is nothing to tell you, “here, this one, this is the problem” because there isn’t any one which is the problem. The problem is an emergent phenomenon.

Any specific checkpoint may be one that you encounter only rarely, or perhaps only once. Consider, for example, all the various procedures we make new hires go through. When you hit such a checkpoint, it may be tedious and annoying, but once you’ve passed it it’s done with. Thereafter you really have no incentive at all to do anything about it, because you’ll never encounter it again. But if we make a large number of people each go through it once, there’s still a large multiplier, and we’ve still burdened our organization with the cumulative cost.

A problem of particular note is that, because checkpoints tend to be specialized, they are often individually not well known. Plus, a larger total number of checkpoints increases the odds in general that you will encounter checkpoints that are unknown or mysterious to you, even if they are well known to others. Thus it becomes easy for somebody without the relevant specialized knowledge to get into trouble by violating a rule that they didn’t even know to exist.

Unknown or poorly understood checkpoints increase friction disproportionately. They trigger various kinds of remedial responses from the organization, in the form of compliance monitoring, mandatory training sessions, emailed warning messages and other notices that everyone has to read, and so on. Each such checkpoint thus generates a whole new set of additional checkpoints, meaning that the cumulative frictions multiply instead of just adding.

Violation of a checkpoint may visit sanctions or punishment on the transgressor, even if the transgression was inadvertent. The threat of this makes the environment more hostile. It trains people to be become more timid and risk averse. It encourages them to limit their actions to those areas where they are confident they know all the rules, lest they step on some unfamiliar procedural landmine, thus making the organization more insular and inflexible. It gives people incentives to spend their time and effort on defensive measures at the expense of forward progress.

When I worked at Electric Communities, we had (as most companies do) a bulletin board in our break room where we displayed all the various mandatory notices required by a profusion of different government agencies, including arms of the federal government, three states (though we were a California company, we had employees who commuted from Arizona and Oregon and so we were subject to some of those states’ rules too), a couple of different regional agencies, and the City of Cupertino. I called it The Wall Of Bureaucracy. At one point I counted 34 different such notices (and employees, of course, were expected to read them, hence the requirement that they be posted in a prominent, common location, though of course I suspect few people actually bothered). If you are required to post one notice, it’s pretty easy to know that you are in compliance: either you posted it or you didn’t. But if you are required to post 34 different notices, it’s nearly impossible to know that the number shouldn’t be 35 or 36 or that some of the ones you have are out of date or otherwise mistaken. Until, of course, some government inspector from some agency you never heard from before happens to wander in and issue you a citation and a fine (and often accuse you of being a bad person while they’re at it). As Alan Perlis once said, talking about programming, “If you have a procedure with ten parameters, you probably missed some.”

In the extreme case, the cumulative costs of all the checkpoints within an organization can exceed the working resources the organization has available, and forward progress becomes impossible. When this happens, the organization generally dies. From an external perspective – from the outside, or even from one part of the organization looking at another – this appears insane and self-destructive, but from the local perspective governing any particular piece of it, it all makes sense and so nothing is done to fix it until the inexorable laws of arithmetic put a stop to the whole thing. A famous example of this was Atari, where by 1984 the combined scleroses effecting the product development process became so extreme that no significant new products were able to make it out the door because the decision making and approval process managed to kill them all before they could ship, even though a vast quantity of time and money and effort was spent on developing products, many of them with great potential. Few organizations manage to achieve this kind of epic self-absorption, though some do seem to approach it as an asymptote (e.g., General Motors). In practice, however, what seems to keep the problem under control, here in Silicon Valley anyway, is that the organization reaches a level of dysfunction where it is no longer able to compete effectively and it is supplanted in the marketplace by nimbler and generally younger rivals whose sclerosis is not as advanced.

The challenge, of course, is how to deal with this problem. The most common pathway, as alluded to above, is for a newer organization to supplant the older one. This works, not because the one organization is intrinsically more immune to the phenomenon than the other but simply due to the fact that because it is younger and smaller it has not yet developed as many internal checkpoints. From the perspective of society, this is a fine way of handling things; this is Schumpeter’s “creative destruction” at work. It is less fine from the perspective of the people whose money or lives are invested in the organization being creatively destroyed.

Another path out of the dilemma is strong leadership that is prepared to ride roughshod over the sound justifications supporting all these checkpoints and simply do away with them by fiat. Leaders like this will disregard the relevant constituencies and just cut, even if crudely. Such leaders also tend to be authoritarian, megalomaniacal, visionary, insensitive, and arguably insane – and, disturbingly often, right – i.e., they are Steve Jobs. They also tend to be a bit rough on their subordinates. This kind of willingness to disrespect procedure can also sometimes be engendered by dire necessity, enabling even the most hidebound bureaucracies to manifest surprising bursts of speed and effectiveness. A well known and much studied example of this phenomenon is the military, ordinarily among the stuffiest and most procedure bound of institutions, which can become radically more effective in times of actual war. In the first three weeks of American involvement in World War II, when we weren’t yet really doing anything serious, Army Chief of Staff George Marshall merely started carefully asking people questions and half the generals in the US Army found themselves retired or otherwise displaced.

A more user-friendly way to approach the problem is to foster an institutional culture that sees the avoidance of checkpoints as a value unto itself. This is very hard to do, and I am hard pressed to think of any examples of organizations that have managed to do this consistently over the long term. Even in the short term, examples are few, and tend to be smaller organizations embedded within much larger, more traditional ones. Examples might include Bell Labs during AT&T’s pre-breakup years, Xerox PARC during its heyday, the Lucasfilm Computer Division during the early 1980s, or the early years of the Apollo program. Each of these examples, by the way, benefited from a generous surplus of externally provided resources, which allowed them to trade a substantial amount of resource inefficiency for effective productivity. Surplus resources, however, tend also to engender actual parasitism, which ultimately ends the golden age, as all these examples attest.

The foregoing was expressed in terms of people and organizations, but essentially the same analysis applies almost without modification to software systems. Each of the myriad little inefficiencies, rough edges, performance draining extra steps, needless added layers of indirection, and bits of accumulated cruft that plague mature software is like an organizational checkpoint.

October 19, 2014

Map of The Habitat World

By now a lot of you may have heard about the initiative at Oakland’s Museum of Digital Arts & Entertainment to resurrect Habitat on the web using C64 emulators and vintage server hardware. If not, you can read more about it here (there’s also been a modest bit of coverage in the game press, for example at Wired, Joystiq, and Gamasutra).

Part of this effort has had me digging through my archives, looking at old source files to answer questions that people had and to refresh my own memory of how things worked. It’s been pretty nostalgic, actually. One of the cooler things I stumbled across was the Habitat world map, something which relatively few people have ever seen because when Habitat was finally released to the public it got rebranded (as “Club Caribe”) with an entirely different set of publicity materials. I had a big printout of this decorating my office at Skywalker Ranch and later at American Information Exchange, but not very many people will have been in either of those places. Now, however, thanks to the web, I can share it publicly for the first time.

We wanted to have a map because we thought we would need a plan for enlarging the world as the user population grew. The idea was to have a framework into which we could plug new population centers and new places for stories and adventures.

The specific map we ended up with came about because I was playing around writing code to generate plausible topographic surfaces using fractal techniques (and, of course, lots and lots and LOTS of random numbers). The little program I wrote to do this was quite a CPU hog, but I could run it on a bunch of different computers in parallel and combine the results (sort of like modern MapReduce techniques, only by hand!). One night I grabbed every Unix machine on the Lucasfilm network that I could lay my hands on (two or three Vax minicomputers and six or eight Sun workstations) and let the thing cook for an epic all-nighter of virtual die rolling. In the morning I was left with this awesome height field, in the form of a file containing a big matrix of altitude numbers. Then, of course, the question was what to do with it, and in particular, how to look at it. Remember that in those days, computers didn’t have much in the way of image display capability; everything was either low resolution or low color fidelity or both (the Pixar graphics guys had some high end display hardware, but I didn’t have access to it and anyway I’d have to write more code to do something with the file I had, which wasn’t in any kind of standard image format). Then I realized that we had these new Apple LaserWriter printers. Although they were 1-bit per pixel monochrome devices, they printed at 300 DPI, which meant you could get away with dithering for grayscale. And you fed stuff to them using PostScript, a newfangled Forth-like programming language. So I ordered Adobe’s book on PostScript and went to work.

I wrote a little C program that took my big height field and reduced it to a 500×100 image at 4 bits per pixel, and converted this to a file full of ASCII hexadecimal values. I then wrapped this in a little bit of custom PostScript that would interpret the hex dump as an image and print it, and voilá, out of the printer comes a lovely grayscale topographic map. Another little quick filter and I clipped all the topography below a reasonable altitude to establish “sea level”, and I had some pretty sweet looking landscape. At this point, you could make out a bunch of obvious geographic features, so we picked locations for cities, and drew some lines for roads between them, and suddenly it was a world. A little bit more PostScript hacking and I was able to actually draw nicely rendered roads and city labels directly on the map. Then I blew it up to a much larger size and printed it over several pages which I trimmed and taped together to yield a six and a half foot wide map suitable for posting on the wall.

As I was going through my archives in conjunction with the project to reboot Habitat, I encountered the original PostScript source for the map. I ran it through GhostScript and rendered it into a 22,800×4,560 pixel TIFF image which I could open in Photoshop and wallow around in. This immediately tempted me to do a bit more embellishment with Photoshop, so a little bit more hacking on the PostScript and I could split the various components of the image (the topographic relief, the roads, the city labels, etc.) into separate images which could then be individually manipulated as layers. I colorized the topography, put it through a Gaussian blur to reduce the chunkiness, and did a few other little bits of cosmetic tweaking, and the result is the image you see here (clicking on the picture will take you to a much larger version):

(Also, if you care to fiddle with this in other formats, the PostScript for the raw map can be gotten here. Beware that depending on what kind of configuration your browser has, your browser may just attempt to render the PostScript, which might not have exactly the results you want or expect. Have fun.)

There a number of interesting details here worth mentioning. Note that the Habitat world is cylindrical. This lets us encompass several different interesting storytelling possibilities: Going around the cylinder lets you circumnavigate the world; obviously, the first avatar to do this would be famous. The top edge is bounded by a wall, the bottom edge by a cliff. This means that you can fall of the edge of the world, or explore the wall for mysterious openings. By the way, the top edge is West. Habitat compasses point towards the West Pole, which was endlessly confusing for nearly everyone.

We had all kinds of plans for what to do with this, which obviously we never had a chance to follow through on. One of my favorites was the notion that if you walked along the top (west) wall enough, eventually you’d find a door, and if you went through this door you’d find yourself in a control room of some kind, with all kinds of control panels and switches and whatnot. What these switches would do would not be obvious, but in fact they’d control things like the lights and the day/night cycle in different parts of the world, the color palette in various places, the prices of things, etc. Also, each of the cities had a little backstory that explained its name and what kinds of things you might expect to find there. If I run across that document I’ll post it here too.

April 29, 2014

Troll Indulgences: Virtual Goods Patent Gutted [7,076,445]

Another terrible virtual currency/goods patent has been rightfully destroyed – this time in an unusual (but worthy) way: From Law360: EA, Zynga Beat Gametek Video Game Purchases Patent Suit, By Michael Lipkin

Another terrible virtual currency/goods patent has been rightfully destroyed – this time in an unusual (but worthy) way: From Law360: EA, Zynga Beat Gametek Video Game Purchases Patent Suit, By Michael Lipkin

Law360, Los Angeles (April 25, 2014, 7:20 PM ET) — A California federal judge on Friday sided with Electronic Arts Inc., Zynga Inc. and two other video game companies, agreeing to toss a series of Gametek LLC suits accusing them of infringing its patent on in-game purchases because the patent covers an abstract idea. … “Despite the presumption that every issued patent is valid, this appears to be the rare case in which the defendants have met their burden at the pleadings stage to show by clear and convincing evidence that the ’445 patent claims an unpatentable abstract idea,” the opinion said.

The very first thing I thought when I saw this patent was: “Indulgences! They’re suing for Indulgences? The prior art goes back centuries!” It wasn’t much of a stretch, given the text of the patent contains this little fragment (which refers to the image at the head of this post):

Alternatively, in an illustrative non-computing application of the present invention, organizations or institutions may elect to offer and monetize non-computing environment features and/or elements (e.g. pay for the right to drive above the speed limit) by charging participating users fees for these environment features and/or elements.

WTF? Looks like reasoning something along those lines was used to nuke this stinker out of existence. It is quite unusual for a patent to be tossed out in court. Usually the invalidation process has to take a separate track, as it has with other cases I’ve helped with, such as The Word Balloon Patent. I’m very glad to see this happen – not just for the defendant, but for the industry as a whole. Just adding “on a computer [network]” to existing abstract processes doesn’t make them intellectual property! Hopefully this precedent will help kill other bad cases in the pipeline already…

March 5, 2014

Two Recipes for Stone Soup [A Fable of Pre-Funding Startups]

There once was a young Zen master, who had earned a decent name for himself throughout the land. He was not famous, but many of his peers knew of his reputation for being wise and fair. During his career, he was renowned for his loyalty to whatever dojo he was attached to, usually for many years at a time. One year his patronage decided to merge with another, larger dojo, and the young master found himself unexpectedly looking for a new livelihood. But he was not desperate, as he’d heeded the words of his mentor and had kept close contact with many other Zen masters over the years and considered many options.

As word spread about the young master’s availability, he began to receive more interest than he could possibly ever fulfill. It took all of his Zen training and long nights just to keep up with the correspondence and meetings. He was getting queries from well-established cooperatives, various governments, charitable groups, many recently formed houses, and even more people who had a grand idea around which to form a whole-new kind of dojo. This latter category was intriguing, but the most fraught with peril. There were too many people with too many ideas for the young master to sort between. So he decided to consult with his mentor. At least one more time, he would be the apprentice and ventured forth to the dojo of his youth, a half-day’s journey away.

“Master, the road ahead is filled with many choices, some are well traveled roads and others are merely slight indentations in the grass that may some day become paths. How can I choose?” asked the apprentice.

The mentor replied, “Have you considered the wide roads and the state-maintained roads?”

“Yes, I know them well and have many reasons to continue on one of them, but these untrodden paths still call to me. It is as if there is a man with his hands at his mouth standing at each one shouting to follow his new path to riches and glory. How do I sort out the truth of their words?” The young master was genuinely perplexed.

“You are wise, my son, to seek council on this matter — as sweet smelling words are enticing indeed and could lead you down a path of ruin or great fortune. Recount to me now two of the recruiting stories that you have heard and I will advise you.” The mentor’s face relaxed and his eyes closed as he dropped into thought, which was exactly what the young master needed to calm himself sufficiently to relate the stories.

After the mentor had heard the stories, he continued meditating for several minutes before speaking again: “Former apprentice, do you recall the story and lesson of Stone Soup?”

“Yes, master. We learned it as young adepts. It is the story of a man who pretended that he had a magic stone for making the world’s best soup, which he then used to convince others to contribute ingredients to the broth until a delicious brew was made. This story was about how leadership and an idea can ease people into cooperating to create great things for the good of them all.” recounted the student. “I can see the similarity between the callers standing on the new paths and the man with the magic stone. Also it is clear that that the ingredients are symbolic of the skills of the potential recruits. But, I don’t see how that helps me.” The apprentice had many years of experience with the mentor, and knew that this challenge would get the answer he was looking for.

“The stories you told me are two different recipes for Stone Soup,” the master started.

“The first caller was a man with a certain and impressive voice that said to you ‘You should join my dojo! It is like none other and it is a good and easy path that will lead to great riches. Many people that you know, such as Haruko and Jin, have tested this path and others who have great reputations including Master Po and Teacher Win are going to walk upon it as well. Your reputation would be invaluable to our venture. Join us now!'”

“The second caller was a humble and uncertain man who spoke softly as he said ‘You should join my dojo. It is like none other and the path, though potentially fraught with peril, could lead to riches if the right combination of people were to take to it. Your reputation is well known, and if you were to join the party, the chance of success would increase greatly. Would you consider meeting here in two days time to talk to others to discuss our goals and to see if a suitable party could be formed? Even if you don’t join us, any advice you have would be invaluable.” The mentor paused to see if his former student understood.

The young master said “I don’t see much difference, other than the second man seems the weaker.”

The mentor suppressed a sigh. Clearly this visit would not have been necessary if the young master were able to see this himself. Besides, it was good to see his student again and to be discussing such a wealth of opportunities.

He resumed, “Remember the parable of Stone Soup. The first man did not. He recited many names as if those names carried the weight of the reputations of their owners. He has forgotten the objective of the parable: The Soup. It is not the names or reputations of the people who placed the ingredients into the soup that mattered. It was that the soup needed the ingredients and the people added them anonymously, in exchange for a bowl of the broth. The first man merely suggested that important people were committed to the journey. I am quite certain that, were you to ask Haruko and Jin what names they have heard as being associated with the proposed dojo, you would find that your name was provided as a reference without your knowledge or consent.”

The student clearly became agitated as the truth of his mentor’s words sunk in. There was work to do before the day was done in order to repair any damage to his reputation that speaking with the first man may have caused.

The mentor continued, “The first recipe for Stone Soup is The Braggarts Brew. It tastes just like hot water because when everyone finds out that the founder is a liar, they all recover whatever ingredients they can to take them home and try to dry them out.”

The mentor took a quick drink, but gave a quelling glance that told the apprentice to remain silent until the lesson was over.

“You called the second man weaker, but his weakness is like that of the man with the Stone from the parable. He keeps his eyes on the goal — creating the Soup or staffing his dojo. Without excellent ingredients, there will be no success; and the best way to get them is to appeal to the better nature of those who possess them. He, by listening to them, transforms the dojo into a community project — which many contribute to, even if only a little bit.”

“Your skills, young master, are impressive on their own. You need not compare yourself with others, nor should you be impressed with one who would so trivially invoke the reputation of others, as if they were magic words in some charm.”

“The second recipe for Stone Soup is Humble Chowder, seasoned with a healthy dash of realism. This is the tempting broth.” And the mentor was finished.

The apprentice jumped up — “Master! I am so thankful! I knew that coming to you would help me see the truth. And now, I see a greater truth — you are also the man with a Stone. Please tell me what I can contribute to your Soup.”

“Choose your next course wisely, and return to me with the story so that I may share it with the next class of students.”

“I will!”

And with that, the young master ran as quickly as he could to catch up with the group meeting about the second man’s dojo. He wasn’t certain if he’d join them, but the honor of being able to contribute to its foundation would enough payment for now. When he approached the seated group, he was delighted to see several people whose reputation he respected around the fire, discussing amazing possibilities. One of them was Jin, who was shocked to learn that the first man had given his name to the young master…

[This is a long-lost post, originally posted on our old site six years go. Once again, the internet archive to the rescue!]

February 21, 2014

White Paper: 5 Questions for Selecting an Online Community Platform

Today, we’re proud to announce a project that’s been in the works for a while: A collaboration with Community Pioneer F. Randall Farmer to produce this exclusive white paper – “Five Questions for Selecting an Online Community Platform.”Randy is co-host of the Social Media Clarity podcast, a prolific social media innovator, and literally co-wrote the book on Building Web Reputation Systems. We were very excited to bring him on board for this much needed project. While there are numerous books, blogs, and white papers out there to help Community Managers grow and manage their communities, there’s no true guide to how to pick the right kind of platform for your community.

In this white paper, Randy has developed five key questions that can help determine what platform suits your community best. This platform agnostic guide covers top level content permissions, contributor identity, community size, costs, and infrastructure. It truly is the first guide of its kind and we’re delighted to share it with you.

Go to the Cultivating Community post to get the paper.

December 19, 2013

Audio version of classic “BlockChat” post is up!

On the Social Media Clarity Podcast, we’re trying a new rotational format for episodes: “Stories from the Vault” – and the inaugural tale is a reading of the May 2007 post The Untold History of Toontown’s SpeedChat (or BlockChattm from Disney finally arrives)

Link to podcast episode page[sc_embed_player fileurl=”http://traffic.libsyn.com/socialmediaclarity/138068-disney-s-hercworld-toontown-and-blockchat-tm-s01e08.mp3″]

October 30, 2013

Origin of Avatars, MMOs, and Freemium

Origin of Avatars, MMOs, and Freemium – S01E06 Social Media Clarity Podcast

The latest episode of the Social Media Clarity Podcast contains an interview with Chip Morningstar (and podcast hosts: Randy Farmer and Scott Moore). This segment focuses on the emergent social phenomenon encountered the first time people used avatars with virtual currency, and artificial scarcity.

Links and transcription at http://socialmediaclarity.net

August 26, 2013

Randy’s Got a Podcast: Social Media Clarity

I’ve teamed up with Bryce Glass and Marc Smith to create a podcast – here’s the link and the blurb:

Social Media Clarity – 15 minutes of concentrated analysis and advice about social media in platform and product design.

First episode contents:

News: Rumor – Facebook is about to limit 3rd party app access to user data!

Topic: What is a social network, why should a product designer care, and where do you get one?

Tip: NodeXL – Instant Social Network Analysis

August 23, 2013

Patents and Software and Trials, Oh My! An Inventor’s View

What does almost 20 years of software patents yield? You’d be surprised!

I gave an Ignite talk (5 minutes: 20 slides advancing every 15 seconds) entitled

“Patents and Software and Trials, Oh My! An Inventor’s View”

Here’s some improved links…

-

I’ve created ip-reform.org to support the “I Won’t Sign Bogus Patents” pledge.

-

Encourage your company to adopt Twitter’s Inventor’s Patent Agreement

-

Support the The EFF on Patent Reform – DefendInnovation.org has a proposal

-

Sequestration has delayed a bay area PTO office, support this bill

I gave the talk twice, and the second version is also available (shows me giving the talk and static versions of my slides…) – watch that here:

August 2, 2013

Armed and Dangerous

[This is a repost from my long-dead Yahoo 360 blog, originally posted August 2006 about events in spring 2002. I decided to recover this posting from the Internet Archive because recent events, 12 years after 9/11, show that the authorities are STILL over-panicking about our security.]

How could I know that singing “Man of Constant Sorrow” in public could be considered a terrorist weapon?

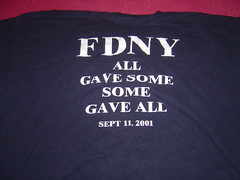

One early spring evening in 2002 I went for a walk in my neighborhood wearing my FDNY September 11th Memorial T-Shirt (shown above), telling my family that I would return just after sundown (about 30 minutes).

About an hour and a half later I arrived at home teasing them by explaining that I’d “ just been handcuffed, interrogated, searched, had a machine gun pointed directly at me, been ordered to my knees two feet from a K-9 gnashing it’s teeth, and was nearly arrested as a terrorist … all just for singing out loud.”

My family didn’t believe me at first – until I showed them the reddened cuff marks on my wrists and the business card of PAPD Sergeant, Sandra Brown.

Now they wanted to hear the whole story…

One mild spring evening in 2002, I felt like singing. I wanted to teach myself some bluegrass and spirituals that I’d discovered recently (mostly as the result of recently seeing O Brother Where Art Thou?) and I felt like being real loud. So, rather than disturb by family, I decided to go for a walk and practice elsewhere. Given the weather, I’d only need a tshirt and jeans to keep me warm until well past sundown. I started singing right away when I got outside, but then noticed some of my neighbors, so I thought that it’d be better if I could find a place to belt out my baritone/bass tones where no one would care if I were in tune. I was practicing, after all.

“The pedestrian walkway over 101 would be perfect”, I thought, “with any luck I’ll be completely drowned out.”

I’d made good time hiking to the pedestrian overpass, humming “Ahhhh am a maaaaan, of con-stant sah-roooow…” along the way. By the time I reached the apex of the passage, the sun was very low in the west dropping just below the hills. The gold-purple sky was an inspirational sight. The constant breeze from the cars whizzing by below was quite effective in carrying my voice away, so I cranked up the volume. I was having a great time and expanded my material to include my favorite Webber show tunes. Other than a pair of guys walking by, my only audience was the late evening commuters most of who had just turned on their headlights. It was a blast. For 15 minutes I was able to belt out anything I wanted, as loud as I could.

When I was starting to feel the effects of singing continuously that loudly the sun had completely set, so I decided to head home. I was running a little later than I’d expected, so I increased my gait a just bit.

As my stride increased (mostly due to gravity) on my way down the sloped ramp back into the neighborhood, directly in front of me appeared two Palo Alto police officers who had just started their way up the ramp. Just a moment after I noticed them, they noticed me, and then did something very, very, strange. They quickly walked backward away from me until they were out of sight, around the corner, at the base of the ramp. I’d never seen anyone do anything like that before. How on earth could I intimidate two police officers just by walking down a pedestrian ramp? As I proceeded down to the exit I called out loud: “HELLO? Is everything alright?”

As I came to the bottom and walked around the corner there were about a half dozen of Palo Alto’s finest, one with what looked like an M-16 and others with pistols pointed directly at me. There was much yelling and I see and hear a dog barking threateningly – “Don’t move!” “Turn Around!” “Get Down!” “Put your hands where we can see them!” “Bark! Bark! [Jangling of a large dog chain.]”

I wasted no time at all, I put my hands in the air and turned my back to them. I kneeled, quickly enough that it hurt. “I think there’s been some mistake, whatever you do, please don’t let go of that dog” is all I could think to say at the moment. I had no idea what the heck was going on, but I didn’t want to give them any reason to make a horrible mistake.

“Who are you?” “Where are you from?” “What are you doing here?” “What are you carrying?” were the rapid-fire questions I can remember. I quickly explained that I was on a walk, singing songs. “The only thing I’m carrying is my wallet, which shows I live two blocks from here”, I said, still kneeling, I didn’t even have my house keys. “Take it out and toss it on the ground, but move very slowly”, said a woman who seemed to be in command of situation, She was to my left, but still behind me where I couldn’t see her. Very, very cautiously, I complied. “Do you have anything else?”, the request was rather urgent and sounded specific. “No. Nothing.”

An officer came up and handcuffed my wrists behind my back, aggressively patted me down, and helped me to my feet. My wallet was retrieved the commander-woman. Once I could face the squad again, I clearly recognized her as Sandra Brown, an officer who had done many hours as a bicycle-beat cop in the downtown Palo Alto area, where my family had spent nearly every Friday evening for nearly 14 years. I was hoping that this meant she might recognize me as well, helping to diffuse whatever this horrible mess was all about.

She walked me over to the back of her police cruiser, pressing me back on the trunk hard enough that my handcuffed wrists were pressed into the car metal enough to let me know that I wasn’t going to be going anywhere without her permission. She grabbed the walky-talky that I hadn’t previously noticed had been set on the roof of the car and spoke into it “(muffled) check in. Anything?”. I couldn’t make out the response, but the meaning was made clear to me immediately when she asked:

“Did you go all the way across the overpass?” “No.”

“Did you see anyone else up there?” “Just two guys that walked by about 20 minutes ago. Nothing unusual.”

“Where did you put it?” “Put what? I didn’t have anything.”

“Did you leave behind any clothing” “Clothing? What? No.”

Fifteen to twenty minutes passed. Officer Brown checked my ID and confirmed that I’m local. She noticed my shirt for the first time. The cuffs were starting to hurt. I’d been told to be quiet. The sturdy, but small blond woman with the assault rifle was keeping it at-the-ready, but it isn’t pointing at me. The dog had stopped barking, but was at some kind of station-keeping pose. Lots more radio traffic. I finally piece together that at least two officers were on the other side of the ramp are looking for something, something that they think I might have hidden there, something critical to this situation.

Finally, the invisible officers at the other end of the radio apparently gave up the search. My heart stopped racing. My temperature started to drop. You see, I finally stopped thinking that I’m likely to end up wounded or dead due to someone panicking.

Once the search is over, it became clear that maybe the situation was not what they had expected/feared. Officer Brown started to explain: “We got a phone call from someone on a cel-phone driving on 101 reporting a sniper, wearing a trench coat, was shooting at cars with a high-powered rifle or machine gun.” Apparently this triggered the Palo Alto equivalent of the swat team.

I couldn’t resist: “An overweight middle-aged man, singing the lead from The Phantom of the Opera (probably waving his arms about, crooning to Christine about being ‘inside her mind’), while wearing jeans and a tshirt that reads All Gave Some, Some Gave All on the back, somehow looks like a Columbine kid terrorizing the freeway with an automatic weapon? What irony: Wear a public-safety-supporting tshirt, get suspected of being a sniper.”. This observation did get a bit of a giggle out of the one with the real Tommy gun, finally hanging peacefully at her side.

I was feeling a little put out: “One call with such a vague description gets this level of response? Did 9/11 really turn us all into people looking for a terrorist behind every darkened corner? A trench coat? This is pretty unbelievable.” I was starting to get very sore about my wrist pain. “We’re sorry, we need to be extra cautious in situations such as these, if it had turned out to be true… In any case, you’ll have a great story to tell your kids and grandkids.”

“True. Can I get out of these now?” There were a few more rounds on the radio, getting a final approval to release me. Rubbing my wrists I share, “You know, my family will never believe me when I tell them that this happened. Do you have one of those Palo Alto Officer trading cards our kids got at school a few years ago?” Turned out that they were out of print, but Officer Brown did have a standard issue business card, which she gave me as they wished me well and I started walking home. [I know I still have it around here somewhere.]

Other than practicing the first of many tellings of this story on the way home, I have never forgotten that the fear generated by the terrorist attacks on 9/11 had changed our world forever. I don’t think that driver would have ever made such are report if this had all occurred one year earlier.

Fortunately for me, the police still are trained to get things right before they themselves start shooting reported terrorists.

“I am a man of constant sorrow. I’ve seen trouble – all my days.”